KARPATHOS - FOLK MUSIC & POETRY

Karpathos

is one of many beautiful islands that grace the Aegean Sea. It has

breathtaking natural beauty and is particularly known for its pristine beaches

which rival the best of the Dodecanese and all of Greece. However, the most

distinguishing element of Karpathos is its people and their deep rooted

culture and traditions. Karpathians are true descendants of Homer. Their

social, spiritual and emotional existence is vividly expressed in their folk

music, dance and poetry all of which have remarkably withstood the test of

time.

Karpathos

is one of many beautiful islands that grace the Aegean Sea. It has

breathtaking natural beauty and is particularly known for its pristine beaches

which rival the best of the Dodecanese and all of Greece. However, the most

distinguishing element of Karpathos is its people and their deep rooted

culture and traditions. Karpathians are true descendants of Homer. Their

social, spiritual and emotional existence is vividly expressed in their folk

music, dance and poetry all of which have remarkably withstood the test of

time.

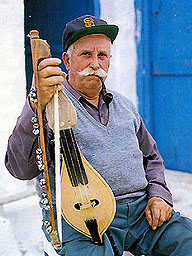

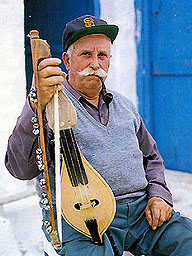

Karpathian music

is played by the descendant of Apollo's lyra which is accompanied by the bag

pipe, called tsambouna, and only in this century by the laouto or lute.

Karpathian dances are unlike most Greek folk dances. They command an imposing

presence and grace through powerful yet austere motion reminiscent of the

dances from Pontos. Poetry, however, has been and still remains the principal

form of emotional and spiritual expression. Karpathians engage in poetry to

lyrically epitomize their private and public lives and emotions.

Karpathian music

is played by the descendant of Apollo's lyra which is accompanied by the bag

pipe, called tsambouna, and only in this century by the laouto or lute.

Karpathian dances are unlike most Greek folk dances. They command an imposing

presence and grace through powerful yet austere motion reminiscent of the

dances from Pontos. Poetry, however, has been and still remains the principal

form of emotional and spiritual expression. Karpathians engage in poetry to

lyrically epitomize their private and public lives and emotions.

Karpathian folk poetry is based on the "mantinatha" which is composed of two,

fifteen syllable, rhyming verses of iambic rhythm identical to Homer's epics.

The mantinatha is still used, to an equal or lesser extent, in other places

such as Cyprus, Crete, Kassos and other islands of the Aegean.

There are two basic categories of mantinatha: (a) those composed spontaneously

and sung in public as part of social and family gatherings, and (b) those

planned and composed privately and communicated in writing. They convey

thoughts and emotions about happiness, sorrow, personal experiences, love and

romance, private, social and even political events.

There are two basic categories of mantinatha: (a) those composed spontaneously

and sung in public as part of social and family gatherings, and (b) those

planned and composed privately and communicated in writing. They convey

thoughts and emotions about happiness, sorrow, personal experiences, love and

romance, private, social and even political events.

In social gatherings such as weddings, baptisms, religious festivals and, in

particular, impromptu parties, Karpathians engage in poetic dialog for hours

and sometimes days. In such parties or "glendia", typically held in coffee

shops or tavernas, participants gather around folk musicians where they

compose and sing mantinathas to each other.

Their spontaneous compositions are sung to folk melodies called skopee. These

melodies vary in length, tempo, and complexity. By most accounts there are

about 40 known skopee some of which are not even identified by name. Singers

master a number of skopee and sing each mantinatha to the tune that best

conveys its emotion and context.

Each singer will sing two to three mantinathas on a topic that is being

deliberated by the "parea" or group of participants. He composes each

mantinatha in real time and most often begins to sing one without quite

knowing how to finish it. Such improvisation is assisted by the way

mantinathas are sung and the extended timing of their melodies. The singer

vocalizes the first half of the first verse which is repeated by the parea in

chorus. The singer then repeats the first half and completes the first verse

which is also repeated by the chorus. He completes the mantinatha by singing

the second verse in the same manner. This conversation in verse is continued

by others until the topic is exhausted and someone introduces another.

The next piece is from a glendi celebrating a

baptism at a picturesque chapel in Mertonas, Karpathos.

The deeply moved

grandfather

sings as his name passes on to his grandchild.

As indicated above, context as well as melody are used as an ensemble to

communicate thoughts and emotions. Some skopee are fast, some slow, others are

sad and others are gay. There are simple ones that are easy to learn, and

quite complex ones that are mastered by the few and very skilled. Skopee are

rendered with small yet significant variations from village to village or

geographical area, but are also heavily influenced by the individual

interpretation of folk musicians and singers. As in american jazz and blues,

improvisation is applied equally to lyrics and music.

Next we have an example of diversity in style and interpretation

in singing and playing the melody of

skopos tis niktas.

The first sample is from Kassos, the second and last samples

are from the villages of Othos and Olympos, Karpathos.

All expressions are true to the basic melody, yet the variation

in style is refreshing.

Notice the slower tempo of the Kassos version and the

emotion of the singer in the last sample.

Next we have an example of diversity in style and interpretation

in singing and playing the melody of

skopos tis niktas.

The first sample is from Kassos, the second and last samples

are from the villages of Othos and Olympos, Karpathos.

All expressions are true to the basic melody, yet the variation

in style is refreshing.

Notice the slower tempo of the Kassos version and the

emotion of the singer in the last sample.

Mantinathas are also synthesized outside of the spontaneous and dynamic

setting of the glendi. They are prepared with care and usually addressed to

loved ones privately, or openly during family events such as baptisms and

weddings. Mantinathas are also prepared and published as commentary or satire

on social and political issues, as well as, historical events. In some cases,

mantinathas are composed as a form of personal diary.

Mantinathas are also synthesized outside of the spontaneous and dynamic

setting of the glendi. They are prepared with care and usually addressed to

loved ones privately, or openly during family events such as baptisms and

weddings. Mantinathas are also prepared and published as commentary or satire

on social and political issues, as well as, historical events. In some cases,

mantinathas are composed as a form of personal diary.

The following is a poem, originally part of a letter from a

mother to her son, expressing her love and longing for his return to the island.

The poem was later set to music and

performed

by Marigoula Kritsiotis from Othos, Karpathos.

As mentioned earlier, Karpathian musical tradition is diverse in style

geographically and interpretation individually. It has, however, been

preserved faithfully and remains practically unchanged over the last one

hundred years. One noteworthy exception reflective of modern times has been

the increasingly faster tempo of dance music.

This is demonstrated on the

pano choros dance:

the slow tempo on the first piece recorded by Baud-Bovy in 1935,

the lavish inflections of Papaminas' lyra in 1976.

and the raw energy of Sofillas in 1995.

As mentioned earlier, Karpathian musical tradition is diverse in style

geographically and interpretation individually. It has, however, been

preserved faithfully and remains practically unchanged over the last one

hundred years. One noteworthy exception reflective of modern times has been

the increasingly faster tempo of dance music.

This is demonstrated on the

pano choros dance:

the slow tempo on the first piece recorded by Baud-Bovy in 1935,

the lavish inflections of Papaminas' lyra in 1976.

and the raw energy of Sofillas in 1995.

Music and poetry identify the Karpathian soul, express its pathos and ethos,

and forge an unbreakable bond with the motherland. They are a live tradition

and an integral part of every day life. Young people continue to engage in

them with respect and enthusiasm. By learning how to sing and dance through

active participation in the traditional glendi, they are helping preserve

tradition and ensure its continuity and relevance.

We will say goodby with the music of another dance called

Sousta performed by

Minas Papaminas in Baltimore, Maryland.

BACK

Pericles Lagonikos

Pericles Lagonikos

(c) Apella Nota, 1998.

Karpathos

is one of many beautiful islands that grace the Aegean Sea. It has

breathtaking natural beauty and is particularly known for its pristine beaches

which rival the best of the Dodecanese and all of Greece. However, the most

distinguishing element of Karpathos is its people and their deep rooted

culture and traditions. Karpathians are true descendants of Homer. Their

social, spiritual and emotional existence is vividly expressed in their folk

music, dance and poetry all of which have remarkably withstood the test of

time.

Karpathos

is one of many beautiful islands that grace the Aegean Sea. It has

breathtaking natural beauty and is particularly known for its pristine beaches

which rival the best of the Dodecanese and all of Greece. However, the most

distinguishing element of Karpathos is its people and their deep rooted

culture and traditions. Karpathians are true descendants of Homer. Their

social, spiritual and emotional existence is vividly expressed in their folk

music, dance and poetry all of which have remarkably withstood the test of

time.

There are two basic categories of mantinatha: (a) those composed spontaneously

and sung in public as part of social and family gatherings, and (b) those

planned and composed privately and communicated in writing. They convey

thoughts and emotions about happiness, sorrow, personal experiences, love and

romance, private, social and even political events.

There are two basic categories of mantinatha: (a) those composed spontaneously

and sung in public as part of social and family gatherings, and (b) those

planned and composed privately and communicated in writing. They convey

thoughts and emotions about happiness, sorrow, personal experiences, love and

romance, private, social and even political events.

Next we have an example of diversity in style and interpretation

in singing and playing the melody of

Next we have an example of diversity in style and interpretation

in singing and playing the melody of

Mantinathas are also synthesized outside of the spontaneous and dynamic

setting of the glendi. They are prepared with care and usually addressed to

loved ones privately, or openly during family events such as baptisms and

weddings. Mantinathas are also prepared and published as commentary or satire

on social and political issues, as well as, historical events. In some cases,

mantinathas are composed as a form of personal diary.

Mantinathas are also synthesized outside of the spontaneous and dynamic

setting of the glendi. They are prepared with care and usually addressed to

loved ones privately, or openly during family events such as baptisms and

weddings. Mantinathas are also prepared and published as commentary or satire

on social and political issues, as well as, historical events. In some cases,

mantinathas are composed as a form of personal diary.

As mentioned earlier, Karpathian musical tradition is diverse in style

geographically and interpretation individually. It has, however, been

preserved faithfully and remains practically unchanged over the last one

hundred years. One noteworthy exception reflective of modern times has been

the increasingly faster tempo of dance music.

This is demonstrated on the

As mentioned earlier, Karpathian musical tradition is diverse in style

geographically and interpretation individually. It has, however, been

preserved faithfully and remains practically unchanged over the last one

hundred years. One noteworthy exception reflective of modern times has been

the increasingly faster tempo of dance music.

This is demonstrated on the

Pericles Lagonikos

Pericles Lagonikos